Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

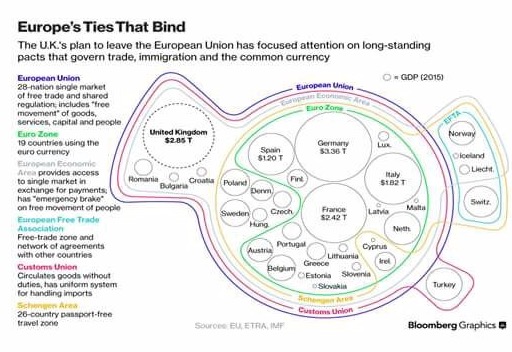

There are few soundbites as inane as Theresa May’s “Brexit means Brexit”, as there are at least 6 options for trading with the European Union. The binary EU referendum choice between Remain and Leave did not provide a mandate for a particular way of Leaving, and the Tories were elected in 2015 on a mandate of ensuring continued access to the single market (which is not the current plan for a hard Brexit). From the most isolationalist position, the UK (or an independent Scotland) can choose to trade via the World Trade Organization (WTO), Multi (or Bi-) lateral Trade agreements, the European Union Customs Union (EUCU), the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the European Economic Area (EEA) (access to the single market) and the European Union (EU) (membership of the single market). Note that NO trade agreements can officially be negotiated before Brexit, potentially leaving a damaging gap.

It is clear that Scotland has no democratic say in this UK, yet has totally different needs from the UK, particularly to do with freedom of movement. Its resources will be bargained away by the UK. In an independent Scotland, it will be the people of Scotland, and their Scottish Government, who will decide our future policy on Europe, and which of the trading options is in Scotland’s best interests.

- WTO: this is where the UK will end up if no deal is done with the EU. It aims to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible”, and deals with regulation of trade between 162 participating countries by providing a framework for negotiating trade agreements and a dispute resolution process. It is sometimes described as a ‘free trade’ institution, but that is not entirely accurate, as it does allow tariffs and other forms of protection – rich countries are able to maintain high import duties and quotas in certain products, blocking imports from developing countries. Tariffs are not always bad things – they can protect endangered industries (e.g. Steel). New membership can take 2-5 years. The UK is already a WTO member (in the EU), but will need years to re-negotiate its membership terms and negotiate new deals with countries it already has EU arrangements in place for. It could not depend on obtaining as good terms as the EU currently has. The only way to avoid lengthy negotiations under WTO rules would be to eliminate the tariffs altogether (like Hong Kong and Macao) but that would be politically difficult, exposing industry to new competition without gaining better access for exporters. Not a good place to be.

- Trade agreements: This (as far as we can see) is the preferred destination of the UK. The EU already has 50 of these in place, with 67 in progress (including the US, Japan and India) as well as Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) to allow goods to be inspected and declared in conformity with Single Market rules (including China, the US and Australia). They generally take years to agree, and any EU deal must be ratified (and can be vetoed) by any of the 28 members (which would allow Spain to veto any deal not making concessions over Gibraltar). Switzerland has negotiated a series of bilateral deals that give it access to the EU single market for most industries, although it also has to apply EU rules, accept free movement and pay the EU money. Other examples are the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and Trade in Services Agreement (TISA). US President Trump has vowed to end NAFTA, TPP and TTIP (unless offered a one-way deal by the UK). These treaties often come with Investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) systems through which multinational companies can sue countries in secret. Trade agreements are NOT free trade agreements, and may pose a threat to a publicly-owned NHS and even to democracy. Freer movement of people is often involved, as Theresa May recently found out in India. Why would the EU negotiate a better deal for the UK outside than inside? It would be suicide.

- EUCU: The European customs union is a principal condition of the EU. No customs duties are levied on goods travelling within the customs union and – unlike a free trade area – members of the customs union impose a common external tariff on all goods entering the union. One of the consequences of the customs union is that the EU negotiates as a single entity (with its 500 million consumers) in international trade deals such as the WTO. The EU is in customs unions with Andorra, San Marino, and Turkey, with the exception of certain goods. If the UK negotiates a good trading deal with the EU, that deal would also apply to an independent Scotland if it is still in the EU. But if the EU makes no deal (or a punitive deal) with the UK, and Scotland stays in the EU, then our access to the rest of the UK market will be restricted.

- EFTA: a 4-member free trade zone with access to the EU’s single market via the EEA: there are no tariffs or taxes or quotas on goods and/or services. Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein are members. Norway is part of the EU’s single market, but it is not part of the customs union, and Norwegian goods (with exceptions for farm produce and fish) are imported tariff-free into the EU. They have to implement EU single market rules and regulations in their own countries, with little say on what they are. Free movement for EU citizens applies to EFTA countries, and they pay into EU coffers in the same way as EU members. Norway has an “open mind” to an independent Scotland joining. In some ways this seems a good first option for an independent Scotland.

- EEA: comprises the EU and Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. The EEA provides for access to the EU’s single market freedoms and members must apply all EU legislation related to them, as well as most EU employment and environmental law. But members would not be covered by EU laws in other areas, notably agriculture, fisheries, tax, justice and home affairs (although Norway and Iceland have signed separate treaties with the EU on these issues). Free movement for EU citizens applies to EEA countries, and they pay into EU coffers in the same way as EU members.

- EU: The EU has developed an internal single market through a standardised system of laws, standards and regulations that apply in all member states, to eliminate tariffs, quotas, taxes on trade, and non-tariff barriers. EU policies aim to ensure the free movement of people, goods, capital and services (though services are still not completely covered) within the internal market, enact legislation in justice and home affairs, and maintain common policies on trade, agriculture, fisheries, and regional development. The EU also has free trade arrangements with many other countries in Europe and beyond – negotiations to establish them can take years.

- Questions remain on EU membership for an independent Scotland – would we be treated as a continuing member, as a successor state to the UK, or as a new member? There is NO queue of other countries to wait behind – fast-tracking is possible. Spain (or any other country worried about their own independence movements) is unlikely to veto an independent Scotland’s EU application.

- Within the EU, there are several options open to members, which are not essential to understanding the trade options (within the Schengen Area, passport controls have been abolished. The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) was established in 1979. A monetary union was established in 1999 (in full force in 2002), and is composed of 19 EU member states which use the euro currency (8 do NOT use the euro, including Sweden, despite having agreed to do so as far back as 1994).

Yes Edinburgh West has a website, Facebook, Twitter, National Yes Registry and a Library of topics on Scottish Politics, including Independence.