Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /usr/home/movgwifi/public_html/yesedinburghwest.info/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Reviewed in The National. Buy the book here.

It was under the auspices of a series of Georges that much of the militarisation of the Highlands was undertaken. The groundplans of a morning’s work at Drummossie Moor are among the most poignant items included in this beautiful and almost compulsively readable book. It tells the story of how our nation’s defences were represented, as often with demonstrative pride as with secrecy, from the time of the Rough Wooing in 1543 to the Cold War. It starts a little earlier than that, even, with James V’s epic sail round the northern reaches of his kingdom, a year-long voyage that required the services of a “rutter” or “routier” to map a safe progress. The tension between utility and aesthetics was early in evidence. A “platt” of Leith, showing the location of mines and artillery on the day the French defenders capitulated on July 7 1560 is part-map, part-diagram, part-landscape painting. Overhead scaled plans were not yet the norm. John Ramsay’s scroll commemorating the Battle of Pinkie in 1547 is reminiscent in style of Ethiopian paintings of the victory over Italy at Adwa in 1896; they can still be bought at stalls in Addis Ababa today. Even later in the story, with aerial surveying dominant, there is still art-historical interest. A detailed plan of Inchmickery in the Firth of Forth is both fantasy island and Vorticist drawing.

The strategic mapping of glens and waterways after Culloden changed the Highlands forever, though not always in the ways usually perceived. Similarly, the construction of great forts, barracks and defensive placements gave fresh energy and subject matter to architectural draughtsmen. There is an air of Masonic mystery and guild-secrecy to many of the images of Fort George, those that admit its existence, that is. William Skinner and Charles Tarrant in 1748 find a halfway place between presence and absence in a beautiful, ghostly plan of Ardersier “with the Design’s Fort as Trac’d Thereon”, “staind in Yellow” as was the custom among cartographers for an as yet unbuilt structure.

“Cartographic silence” – it is often what maps fail to show that is most interesting. What would the Kaiser’s agents have made of pre-First World War Ordnance Survey six-inch-to-the-mile maps of Ross and Cromarty which show the Ardersier peninsula as essentially empty space? Would Admiral von Knorr really have been fooled by this, given that Fort George, probably the most impressive military building in the British Isles, occupied forty two acres and could house two infantry regiments? Would he have noticed that the OS had failed to remove a reference to “Rifle Ranges” nearby? Would he have wondered about the large road that seemed to lead nowhere? Or would be have screwed in his monocle, traced the dotted line that crosses the Moray Firth narrows from Chanonry Point and read, quite clearly, “Fort George Ferry”?

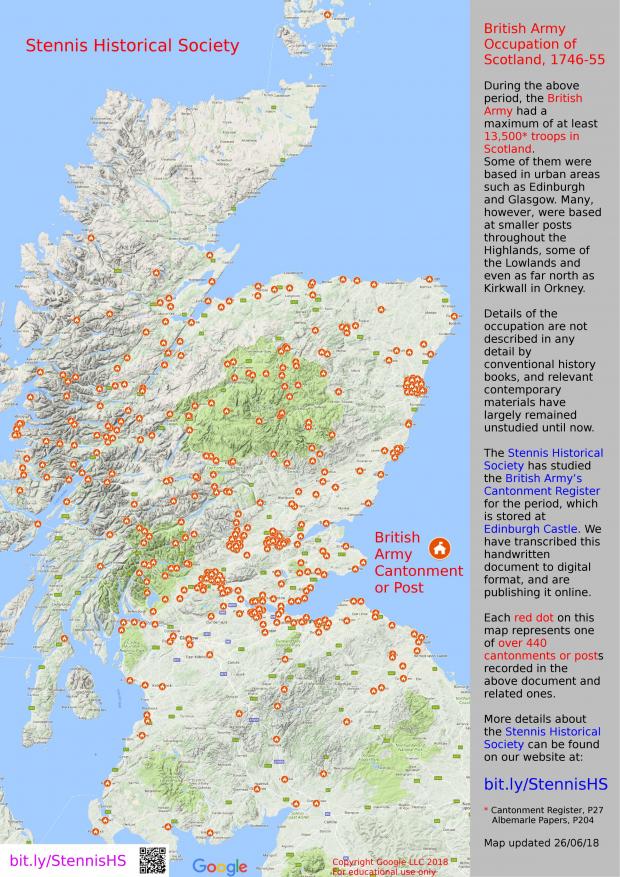

A brilliant example of the powers of a map to tell a story is the map of the British Army occupation of Scotland post-1745, produced by the Stennis Historical Society of Edinburgh.

Yes Edinburgh West has a website, Facebook, Twitter, National Yes Registry and a Library of topics on Scottish Politics, including Culture.