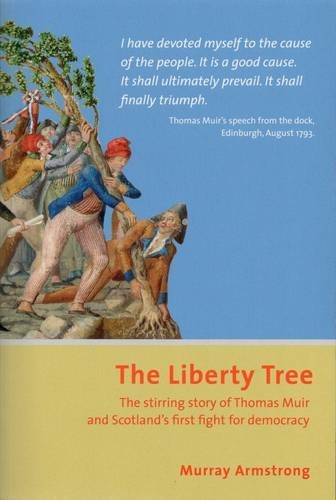

Kenny McAskill reviews The Liberty Tree – The Stirring Story of Thomas Muir and Scotland’s First Fight For Democracy

Kenny McAskill reviews The Liberty Tree – The Stirring Story of Thomas Muir and Scotland’s First Fight For Democracy

http://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2014/12/18/the-liberty-tree Buy the book here.

Old Calton cemetery looms over the old town of Edinburgh. Dominating it is the Political Martyrs’ Monument to Thomas Muir and four fellow Friends of the People Thomas Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Neither the cemetery nor the Monument are known to many though the sight is visible to all. The Obelisk is stark and clearly evident from the office of Justice Secretary in St Andrews House. Engraved on it for those who venture in to read are the words “I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause. It shall ultimately prevail. It shall finally triumph”. They were spoken from the dock by Thomas Muir in 1793 when he faced charges of sedition and was sentenced to transportation for 14 years to Botany Bay along with his friends. Though the tale is of all the Friends it is Muir who understandably takes pride of place.

I had heard of him prior to being able to view the monument from my former office. His story has been told before but as with so much of Scotland’s radical tradition it is largely unsung and sadly neglected. There had even once been a Thomas Muir Society for labour lawyers though it appears to have fallen by the wayside. Muir himself was an Advocate, and hence the society, and though the legal profession in Scotland is more noted for its conservatism than its radicalism he bears witness to a seam within it.

The author Murray Armstrong has done a great service in his tale of both the man and the times he lived in. It is a story that deserves to be told and times we need to recall and perhaps even learn from. After all, the subtitle to the book is “The stirring story of Thomas Muir and Scotland’s first fight for democracy”. We’ve lived through another battle in recent years and there are more to come. Armstrong is an exiled Scot from Airdrie now based in London. He’s a journalist to trade not an historian. He makes that clear at the outset but has nothing to apologise for in my view. Retiring as associate editor of the Guardian he has used his time well and productively. He has researched extensively both in his native land and elsewhere giving the book content and substance to add to the sketchy outline that many readers may already possess of Muir and those turbulent and revolutionary times. So there’s sufficient gravitas as well as footnotes for those interested in the research methodology and references to justify it as a work of history.

However, what Armstrong brings in abundance is his skills as a journalist, which add colour and depth to what might otherwise be a worthy tomb. Many a fine historical work can be rather dry. But not so this one. He acknowledges and details the aspects that are fictional but they I believe add to not detract from the book. They are within legitimate licence and based on incidents so long past as to be without oral or written record. The authors’ imagination and journalistic licence, therefore, make it a fast-moving and exciting story adding to rather than detracting from the historical facts. And rightly so as the tale of Muir is itself almost a Boys Own adventure and the times were fascinating not simply in Scotland but around the globe as the waves caused by the French revolution lapped ashore.

Armstrong does well to weave the twin stories of Muir and the times through the book. Both are separate but linked and one cannot be told without the other. The man and his story are after all reflective of the times in which he lived. The juxtaposing of the era with the man is done well. Chapters interchange to some extent between the human interest side and the chronological narrative though also mentioning the plight of friends and comrades. As with the mixing of fact and fiction the book benefits from the synergy between Muir and a wider historical record.

The author starts each chapter with a piece of poetry, prose or a snippet from the time which both is a nice touch and sets the tone. Ironically, it reminded me of Thomas Pakenhams book on the 1798 rebellion “The Year of Liberty” which does much the same but from an Irish rather than Scottish context. Ironically, Muir died just as the rebellion was being brutally suppressed but had met with Wolfe Tone and allied himself to the United Irishmen.

It is both a ripping yarn yet also a testimony of the turbulent times. Muir died just 33 years old and in many ways was an accidental hero. He was the fall guy for Establishment repression rather than a revolutionary insurrectionist in his own right. He did though rise to the occasion when persecuted acting with courage and dignity throughout. Though seriously wounded by a Royal Naval shell forcing him to wear a mask for his later few years he neither raised a pike nor waved a cutlass. Instead he used his legal skills and oratory to articulate the cause of reform and liberty and defend himself and others from injustice.

He came from relatively humble origins with the family house at Huntershill in Dunbartonshire and the business in Glasgow’s Merchant City. Born in 1765 by the time he graduated from Glasgow University America had won its Independence and the likes of Tom Paine who he got to know were advancing the cause of reform and liberty. Muir was a man of conviction. Travelling to both revolutionary France as well as Ireland brought him into contact with great names from that time such as Paine and Tone but also, dangerously for him, to the attention of others. He was targeted by the Establishment and pursued with a vengeance by the troika of Henry Dundas the Home Secretary, his nephew Robert Dundas the Lord Advocate and the Lord Justice Clerk Lord Braxfield. Muir who had great faith in justice and law throughout his life was persecuted by a system hell-bent on his destruction and prepared even to judicially create the crime of which he was convicted. That he did not lose faith in either law or justice is testimony to the decency of the man and the uses that the law can allow even to revolutions. As the great South African Judge and anti-apartheid activist Albie Sachs said centuries later “While one should always be sceptical about the laws pretensions, one should never be cynical about the laws possibilities.”

Following his arbitrary conviction in 1794 the adventures really began. From Edinburgh he was moved to Newgate goal, London; then transported on to Botany Bay. Escaping he travelled via the South Sea Islands to the west coast of America; and from there to Spain via Mexico and Cuba. His journey ended in France where he died in Chantilly just north of Paris on 26th January 1799. A significant journey itself in the 21st century, but a truly incredible one in the late 18th century.

The author paints a sympathetic picture of the man and rightly so as it’s not just his travels that impress but the adventures and engagements along the way. He leaves France just as the Terror begins. He’s in Britain as fear of revolution stalks the establishment and in Ireland as rebellion is brewing. Enduring Dickensian jails he sees the ill-treatment of prisoners to and aborigines in Australia. Badly wounded on a Spanish ship as the old world went to war he’s given citizenship and sanctuary in revolutionary France. The people he meets are recorded as well as the places he visits. Tom Paine and Wolfe Tone join Talleyrand and countless others. The times are chronicled as ordinary people see the chance of a better and fairer land; as the establishment lie and cheat to deny change; as revolutionary backbiting, infiltration by spies and much more strike movements and revolutions in Britain, Ireland and France; and as rebellion is crushed hope extinguished for a while but as history also records not for ever.

So it’s a right good read about a brave man and revolutionary times. The story of the man is worthy of a book itself but it is enhanced by its description of the turbulent times in which he lived. Are there any lessons for us today or about what we’ve just gone through in the referendum? Not really. It was fascinating to read of the planting of Liberty Trees and the fervour throughout the Scotland even in places neither now or then noted as hotbeds of radicalism whether Fochabers or Auchtermuchty. It was also interesting to note that Muir and many others, not initially driven by the cause of independence, saw greater opportunities and less opposition for radical change north of the Border. Plus ca change, plus le meme chose!

Yes Edinburgh West has a website, Facebook, Twitter, National Yes Registry and a Library of topics on Scottish Politics, including Independence.